Haslar creek – where it all started

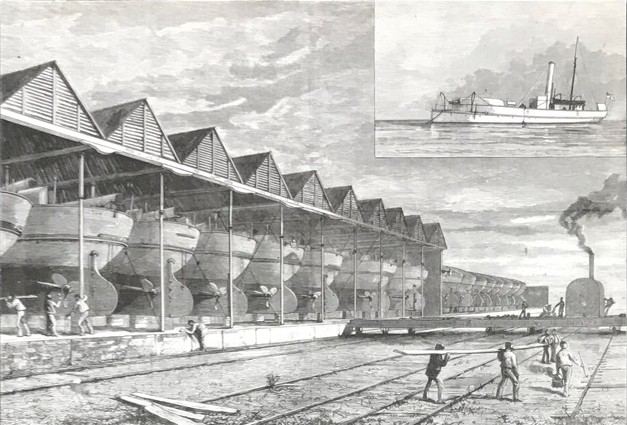

The Haslar Gunboat Yard in Gosport opened in 1856 when the Admiralty clutched into the maritime ramifications of the Crimean War. The gunboats remained there for twenty years as we worried about the Russians.

Haslar Gunboat Yard in 1872 – waiting for the Russians!

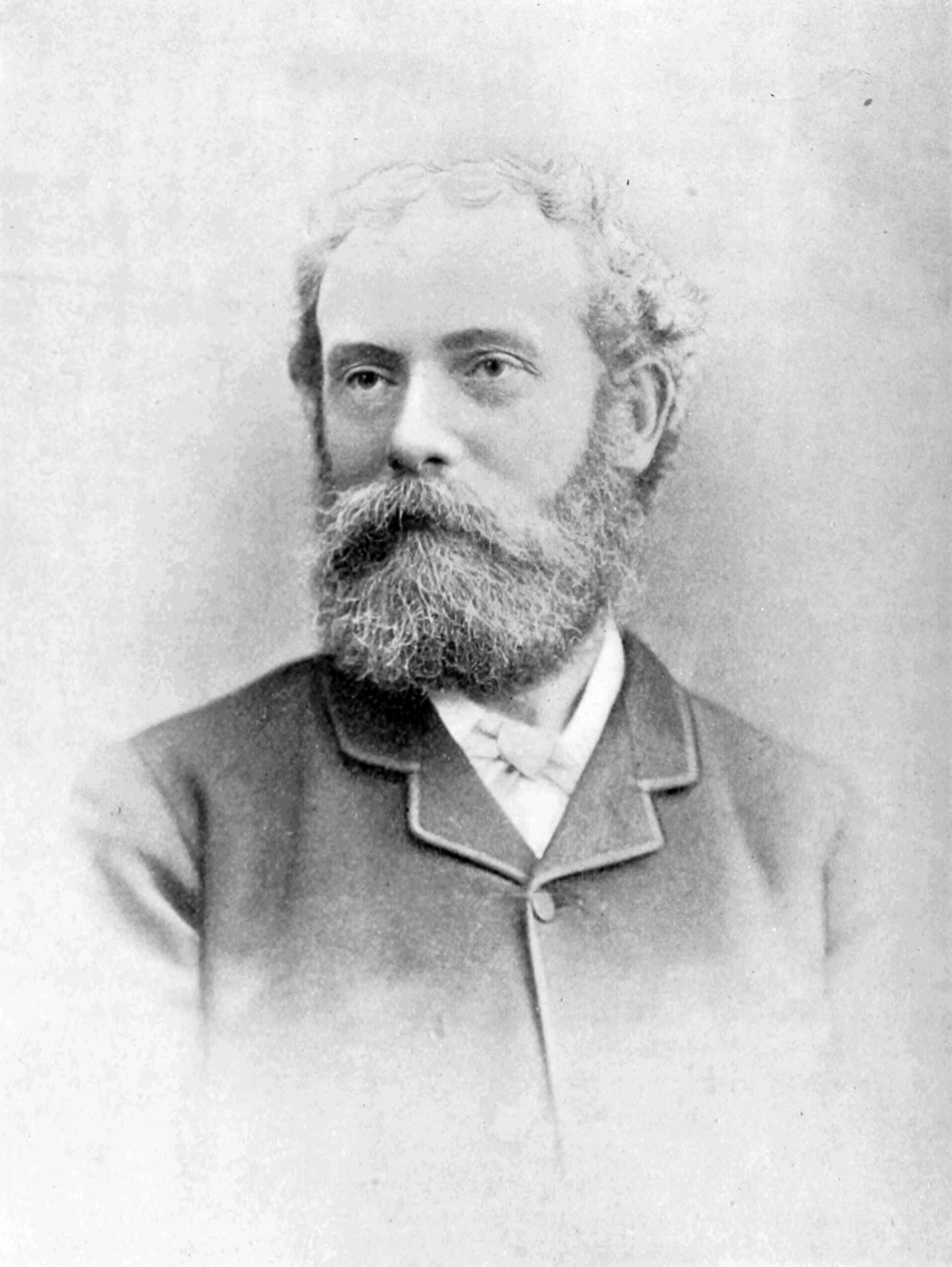

The threat of war has always stimulated new technology and in 1876, HMS Lightning was the first torpedo boat in the world. For a while, she was also the fastest warship in the world at around 23 knots and she was based in Haslar Creek. She was designed by John Thorneycroft, who was subsequently involved in some of the most groundbreaking technological developments of the twentieth century – the emergence of the planing hull, hydroplanes, high power-to-weight petrol engines and high speed propellers.

Much of the testing work was done in some brand new test tanks first installed at Haslar in 1887 and at Thornycroft’s home in Bembridge on the Isle of Wight. Primarily interested in all things maritime, he was distracted for a while at the turn of the century and turned his attention to steam-powered lorries.

But the arrival of the petrol engine allowed Thornycroft to develop a single step hydroplane hull and in 1910, he built a 25 ft boat called Miranda 4, capable of an astonishing 35 knots.

T

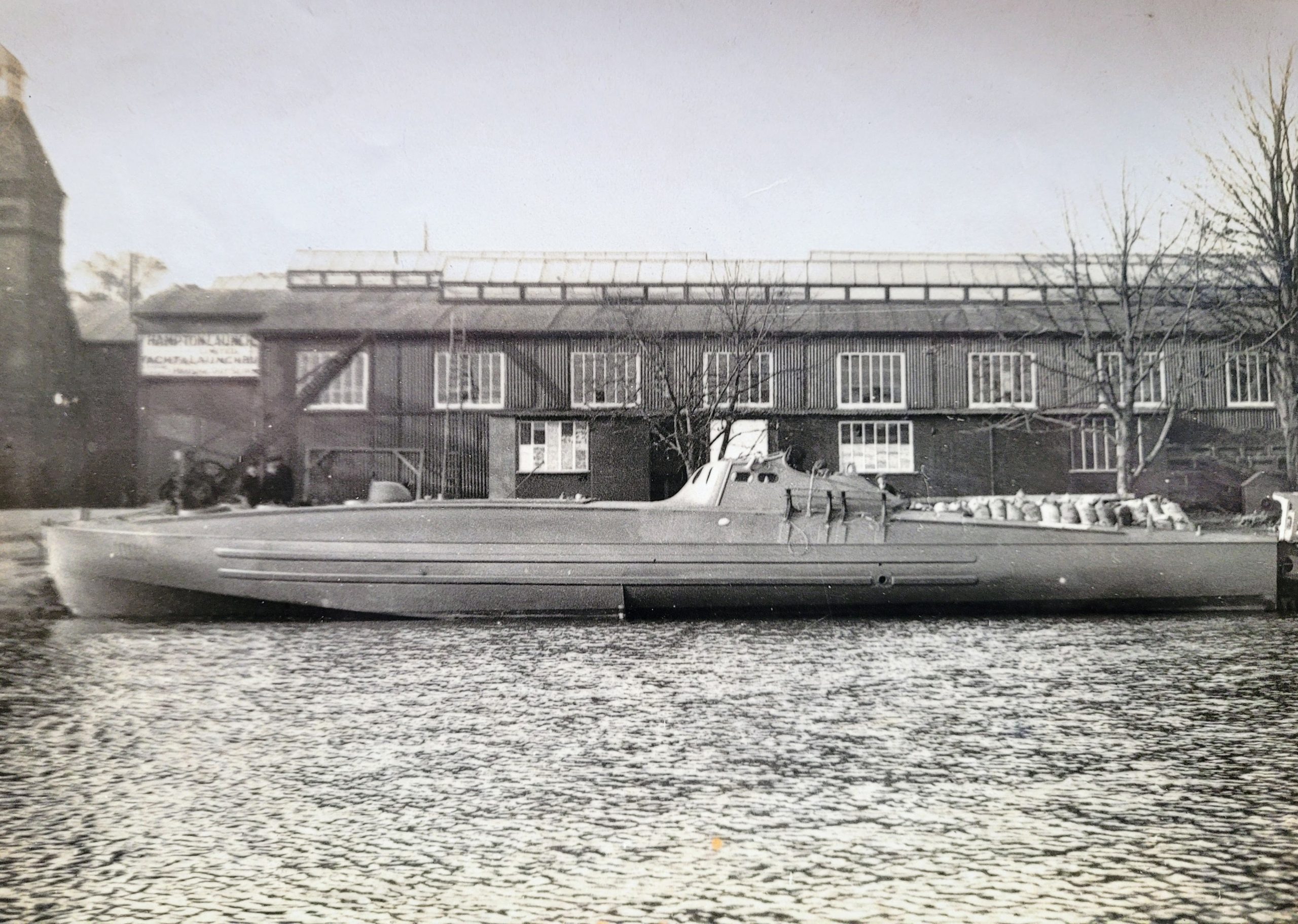

Here’s a picture of CMB1, a 40 footer on the first set of Admiralty trials on the River Thames in 1915. Note the chap in the bowler hat. He appears in many photos of fast boat trials from the first world war. I wonder how he held it on?

Around 40 were built. Thorneycroft went on to build around ninety 55 footers and a dozen 70 footers. A number remained in service with the Royal Navy until the mid 1940s.

The Coastal Motor Boat

Which came first, chicken or egg? In the world of high speed power boats, this is a key question. Efficient hulls… or lightweight, high performance engines? And what about propeller technology?

Just as things do today, sometimes good things come all at once. We tend to think of Karl Benz in 1879 and Rudolf Diesel in 1892 as the pioneers of petrol and diesel engines. They revolutionised sea power for smaller vessels just as the steam engine had done for big ships a century earlier. By 1900 the race was on to improve power to weight ratios, reliability, resistance to sea water…

In parallel, inventors like John Thornycroft were adapting hull shapes to take advantage of undreamt of amounts of propulsion power. Pushing water out of the way takes a lot of energy, so he and his daughter Blanche (the first woman to be elected to the Royal Institute of Naval Architects) set their minds to solving the problem.

Towing scale models up and down a carefully instrumented pond in their garden – later constructing a full scale test tank which you can see today – they searched for ways to reduce drag. The answer was a substantial step cut into the hull a third of the way back from the bow. It introduced air under the back of the boat, lifting it out of the water enough to gain a clear advantage.

The Navy was interested, particularly because of the rise of the German fleet.

The Coastal Motor Boat was borne. The original version carried a single torpedo and , could reach speeds of 39 knots. It was designed to be dropped off by a passing cruiser off Heligoland (it weighed just 4 1/2 tons fully loaded) and run in at speed towards Wilhelmshaven, where the German fleet routinely lay at anchor amid the shoals waiting for the tide.

The crew of three sat on the fuel tank and ran straight at the target, breaking off at 400 yards, pushing the torpedo off the back with a small cordite charge. They would then turn hard to starboard before they rammed the target themselves. Turning to port was almost impossible at speed because of the torque in the propeller. The manoeuvre was executed successfully at the battle of Zeebrugge in 1918. Squadrons of these boats patrolled the Dover Straits and the approaches to Chatham, Portsmouth and London.

The original 40 footers were a bit small; 55 feet seemed to be the optimum and a number of larger ones entered service.

But as the First World War ended, so did the Admiralty’s interest in Coastal Forces and many were paid off. Some were converted to become radio-controlled uncrewed vessels. Others were sold to foreign Navies and the Thornycroft production line ran on until 1940.

The most famous Coastal Motor Boat was CMB4. Read her extraordinary story here.